Stop the Empire Station Complex: Penn Station’s Ghost Still Haunts New York

The following editorial, slightly edited, appeared in the New York Daily News, Oct. 7, 2021

by Josh Alan Friedman

Midtown Manhattan is facing its most important land use decision since the destruction of Penn Station 58 years ago. I’m talking here about the soul of the streets, not just the infrastructure or politics. Cuomo’s Empire Station Complex project grants Vornado Realty Trust the rights to break zoning codes and construct 10 more glass towers, declaring the Penn Station area “blighted.” As a solution, they want to clear cut the neighborhood. This would make generic dead space out of the sidewalks of New York. It would displace hundreds of small businesses, evict residents and demolish midtown’s finite number of historic buildings.

Twentieth century New Yorkers, like myself, who grasp at remnants of the great Land of Oz are in continual mourning. Olde New York has been under siege for two centuries. Unlike in the capitals of Europe, each generation here suffers the bull-dozing of its landmarks. I can no longer enter the beloved stadiums, restaurants or movie theaters of my grandfathers.

The mystique of old Penn Station in the early 1960s was not lost on me as a child. On trips to the city from Long Island, I thought if I ever lost hold of my mother’s hand, I’d be lost forever. A Yogi Berra Yoo-hoo sign in Astoria was the last image commuters saw before the train submerged into total darkness under the East River, careening and squawking like a cart in a Coney Island spook house. The instant the train door slid open at Penn Station, the underground bowels of the city hit you square in the face. The smell of grime and hot dog counters and Con Edison steam vents. No Spitting signs warned of $25 fines. Yet there were stains on the landing where a million violators had rudely ejected chewing gum.

At old Penn Station, I remember the unmistakable face of Morgan Freeman, smiling broadly behind the counter at Nedicks’s serving hot dogs. It was the young actor’s first job fresh from Mississippi. I saw Nedick’s hot dog waitresses make surreptitious appointments with LIRR commuters. Some were hookers. A dozen city newspapers hot off the press were hawked by newsies, while shoeshine boys gave spit shines amidst the steampunk ironworks and choo-choo trains. In the diminished rathole of Penn Station, I long considered Penn Station Magazines the greatest newsstand in the city.

I realize these sentiments don’t translate into today’s real estate dollars. But at stake in Penn Station’s neighborhood are a thousand budget rooms at the Hotel Pennsylvania, beacon to a million tourists who otherwise couldn’t afford the city. (Their phone number is still “PEnnsylvania 6, 5000,” the Glenn Miller hit of 1940, which still plays when you call for a rez. For many years, I received my haircut from a chatty Italian immigrant barber below the lobby.

Among 50 buildings at risk for demolition under eminent domain are three churches that have evaded landmark status: The gothic St. John the Baptist, built in 1872, the storybook St. Francis Roman Catholic Church, built in 1891, and St. Michael’s, built in 1905. Historic structures that would be wiped off the map include The Stewart Hotel, the Penn Station Powerhouse (the last remaining vestige, built from the same granite), the Penn Terminal, Equitable Life Assurance, and Fairmont buildings. During my childhood, there was a secret back-issue magazine warehouse next to the Gimbel’s skybridge (under threat of demolition). They served up old issues of Famous Monsters and Mad to astonished kids like me. Likewise, at Willoughby’s Camera Emporium (founded 1898), I purchased my 8mm Castle films, 200-ft. edits of Universal horror classics.

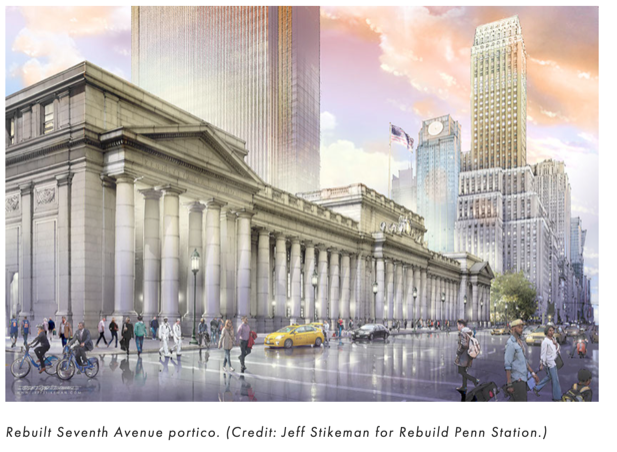

“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us,” said Churchill. He was asking that they rebuild the House of Commons exactly as it had been before the Nazis bombed it. It may be a pipe dream to rebuild the original Penn Station (1910-1963), the lost Beaux-Arts masterwork from architects McKim, Mead, and White. Old world stone masons that created pre-War structures no longer exist. But the Empire Station Complex will grind the remaining funky streets around Penn Station into pablum. It enriches only Vornado Realty, who already refers to the area as “the Vornado campus.” The glut of empty office space would be a curse on the city. Like Hudson Yards, the 10 glass towers they propose are future slums of the sky. I shudder to think how badly they will age, compared to pre-War buildings of stone.

In defense of the streets, I say these grand structures deserve rehabilitation, not annihilation. The demolition of Penn Station is now acknowledged as New York’s greatest architectural crime. Bulldozing the remaining blocks around it would reopen the wound. New Yorkers are oblivious to the mass scale wrecking of midtown in store if ex-governor Cuomo’s plan goes through. The decision rests not in the hands of local citizens, but with Albany legislators.

I pray the entire Empire Station Complex is stopped cold. Private groups like ReThinkNYC and New Yorkers for a Human-Scale City have floated cheaper and better alternatives. Scrap the subsidies to Vornado, scrap the $16-billion in junk bonds. Rebuild Penn Station as the center of a regional unified train network. Hopefully, one that would resemble the picturesque hub of a railroad, not a shopping mall. It is up to Albany to spare the city the insult of another hyper-developed, gentrified glut of glass towers that would dwarf Hudson Yards.

Josh Alan Friedman is the author of Tales of Times Square, and can be found at BlackCracker.fm