The Day I Didn’t Meet Lennon

In August 1965, at nine years old, I was presented an opportunity to meet John Lennon. This was put forth by Tom Maschler, John’s editor at Jonathan Cape, where A Spaniard in the Works was just coming out. Spaniard was Lennon’s second book, following In His Own Write. Maschler was also the English edition editor of my father’s novel, A Mother’s Kisses. My parents and I stayed at Edna O’Brien’s home that week. She had just written August Is a Wicked Month.

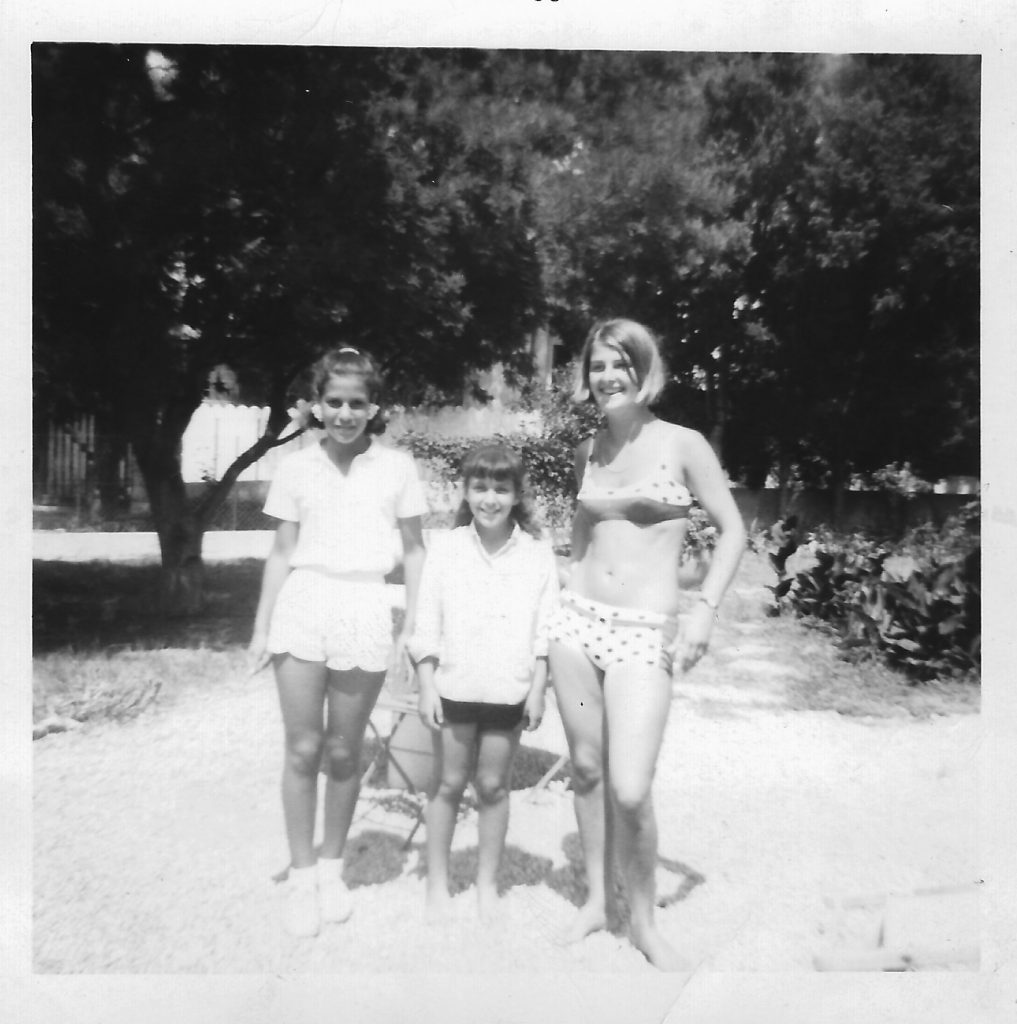

A bigger Beatle obsessive did not exist, as you can see from a photograph of me in August ’65, the hour that I left to meet John. The Beatles dominated my dreams. I was determined to ask if I could join the group.

During summer a year before, when I was 8, I would stare out at the Atlantic Ocean from Fire Island, at the edge of the surf, imagining they lived right across. Them and Gerry and the Pacemakers. We took a sand taxi to Ocean Beach for the opening night of A Hard Day’s Night, during the long hot summer of ’64. I screamed aloud at closeups of the Fab Four onscreen. Now, the next summer, my family rented a villa in Cap D’Antibes, on the French Riviera. I was finally across the ocean, that much closer to them. Still, they were in England, not France.

But toward the end of August, my parents decided to take me, the oldest son, for a week in Paris and London. Drew, Kipp and Piper the cat were left in the care of our own torturous Mrs. Sullivan. I was 9 years old and going to London where the Beatles then lived. Closer.

We stayed at the home of Edna O’Brien, in Putney on the Thames. O’Brien had two sons my age, Sasha and Carlo, who would be my playmates. I was shocked by British food, all of which was unedible to my American palate. The milk was surely not homogenized and tasted rancid on my cornflakes. Fish ’n’ Chips were grungy. Is this what the Beatles ate? I instigated a butter-throwing fight at the dinner table with the two boys, before their nanny. One night, a babysitter came to mind the three of us while our parents went out on the town. One of the boys greeted the mousey Irish babysitter at the door with, “You’re not full of the Jesus crrrap, are you?” Edna O’Brien had to console her as she began to cry.

Sasha and Carlo had a “poor” friend named Bruce. Bruce was a cockney lad, and he was trouble. I was naturally drawn to him, and was allowed to wander off and spend a day with his poor cockney gang.

“Can he do a big kid over?” asked the gang leader.

“Well, he can sure do me,” said Bruce. (We hadn’t fought, he just surmised.)

“Well, then, put ’er there,” said the leader, offering his handshake. The kids barreled down the street singing:

Hitler, has only got one ball

The other is in the Albert Hall

His mother, the dirty bugger

Cut off the other, when he was only small

I told them that America won the War, and was puzzled to hear them say No, they, England, won the war. Back home, we were taught that America won World War II. The gang performed hijinks routines, like nicking candy from the corner store. What I never forgot was how this gang of cockney kids enacted the old slapstick routine where they confounded an old constable guarding a private park. One kid bent down on all fours behind the constable, while another shoved him over. I’m not exaggerating. Then we all ran wild onto the grounds.

One day, at Harrod’s department store with my parents, we saw Mick Jagger tearing through the aisles, being chased by a gaggle of girls. Again, just like in the movies. This summer the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” dominated the London airwaves, followed by “You Really Got Me,” and “Satisfaction.” The music was magic. Back in France, I danced every night with Vicki and her sisters from Switzerland, who lived in the villa across from ours. The whole summer was paradise.

But it was getting toward the end of the week, the end of the summer, and still no Beatles. And then, something miraculous happened. My parents liked to dazzle me with big surprises. Tom Maschler, my father, Bruce Jay Friedman’s editor, invited us to the offices of Jonathan Cape to meet John Lennon at an editorial meeting. It would be our last day in London—just my parents, Bruce and Ginger, and me in Maschler’s office. My 9-year-old mindset regarded this as fate—I thought, of course I’ve been invited to meet John, what took so long.

The next day I was Beatled to the bone, with my Beatle boots and a Boy Scout camera around my neck (I was not a Boy Scout). I invited Sasha and Carlo to come with me to meet John. To my astonishment they preferred to go to “the Baths” (pronounced baahths, an indoor London pool). I was sincerely worried that I would faint when John Lennon walked through the door. But brave enough to chance it. I still intended to ask if I could join the band.

And so, there we were in Maschler’s office. He put a stack of John Lennon’s doodles in my lap. I remember dozens, if not a hundred. Among the reprinted sketches were, I’m pretty sure, originals. Maschler said John doodled everywhere during editorial meetings. And though my nerves were on edge as I watched the door, I apparently was babbling.

“Do shut up,” said Maschler. My parents would repeat this line for years, whenever I wouldn’t.

Maschler made a call. There before me Maschler was on the phone with John Lennon, who apologized. He was having a pool put in that day at his new house and said he had to direct the workers. He would not make the meeting.

And so, I left with a stack of drawings, as well as a signed copy of Spaniard.

Apparently, Maschler didn’t deduce that John’s childish doodlings would someday become valuable as Renaissance art. Over the next few years, my brother Drew and I doodled incessently over John’s original art, scattering all to the winds. Pity, because Drew Friedman did his own drewings over them, giving the doodles a double edge.

I don’t remember being heartbroken that John didn’t show—but rather relieved because I probably would have passed out.