Thunder Road Bites the Dust

Originally appeared as “The Saga of Jacksboro Highway,” in Gallery, March 1989

Driving up the bend of Jacksboro Highway, retired cowpokes squint their eyes upon a familiar landscape unchanged in 50 years. It is the sepia-toned Massey’s 21 Club and the Rockwood Motel, a 1930’s motor lodge, surrounded by green hills and bathed in a massive horizon. Old farmers and former Fort Worth rodeo cowboys mosey on in around happy hour. This is the same bar they’ve been drinking at since they were young and wild, when Jacksboro Highway was known as “Thunder Road”—a 16-mile stretch between Fort Worth and Azle, Texas.

Jacksboro Highway attracted the meanest white people in all of Texas. Outlaws hid there and gangsters flourished within the 40-odd honky-tonk beer joints and lavish nightclubs. The 16-mile stream of neon offered a proliferation of illegal slot machines, backroom gambling, whores, dope, booze and constant shootouts.

By 1990 the Highway Department will be razing Massey’s 21 Club, along with most of the remaining old honky-tonks along the Jax.

Massey’s was one of the safer spots. Proprietor Bobby Sitton promised his father-in-law, Hubert Massey, he’d keep the club looking the same as it did in the 1930’s. He’s kept his promise.

“I really don’t know why,” says Bobby, “but back in those days there was a lot of mean people around. ’Course, most of ’em all been thinned out. Stabbed to death, car wrecks, shot, dynamited or still in the pen from back in the old days. Very few of ’em just flat died.”

Sitton, 56, grew up on the Jax, and talks friendly as apple pie. Yet he’s bowlegged and battle-scarred, with knife scars across the belly. He’s been shot twice in local bars and he's “got stitches on top of stitches” across his head, where countless beer bottles have crashed.

“When you own a club on the Jacksboro, you may be the owner, but you’re always the bouncer,” says Sitton. His hands seem constructed like large, puffy fists. He scratches his head, bewildered as to why Jacksboro was more violent than other places on Earth.

“When we were growing up out here, it just seemed like the thing to do was fighting. Mostly just good ol’ fist fighting, no guns or knives. Worst thing was a beer bottle on the head. Get out there, pick a fight, have a good knockdown drag-out. I’ve been beat on all my life.”

The most troublesome problem Bobby now faces is the loss of his club and the old motel behind it, The Rockwood. Massey’s rose from the base of a street-car diner in 1934. It is like a western version of Sardi’s on Broadway, deserving of landmark status. Red-leather bar stools are built into the counter. Old silver beer refrigerators align the tender’s side of the bar. The seating booths are made of cozy red leather, each fitted with a Seeburg Consolette jukebox. Massey’s water still comes from a well dug out by Bobby’s father-in-law. (“Best well water you ever drunk in your life,” Sitton proudly points out.) His handsome mother-in-law, with a regal beehive, lend class to the joint, bantering with old customers at the bar. Today, she speaks with Billy Ray Robinson, owner of the Arabian-baroque Caravan Motel up on the corner, which his daddy and uncle built. He’ll lose his land to the highway, too.

You expect Clark Gable to swagger in for a cup o’ Joe; a gum-snappin’ Jean Harlow to strut over and jot down your Old Bushmills order on a pad. Like most owners of rough-and-tumble joints, Bobby Sitton will sooner stress his gentle nature. His role model in the art of behaving like a gentleman was Hubert Massey, whose family also founded Fort Worth’s greatest chicken-fried steak restaurant on Eighth Avenue.

“A genuine statesman and gentleman,” says Bobby, who watched his father-in-law offer countless gangsters a free drink with the condition they “call it a day and leave.”

“This club is a family place, where ladies wear dresses and dance to the old-fashioned waltz. We don’t allow any known criminals, prostitutes or dope dealers to come in here.”

On weekends, Massey’s features country-and-Western dancing to the seasoned Jacksboro Highway Band. Leon Short, the 52-year-old lead singer, is the great-great-grandson of Luke Short, who gunned down Marshall Longhair Jim Courtright (a former outlaw himself) outside the White Elephant Saloon on Hell’s Half Acre in Fort Worth, about two miles from the saloon’s current location. “Blasted off the sheriff's thumb,” says Bobby, as if he saw it, “so he couldn't shoot—then blew him away.”

One of the legendary survivors of the old Jax, Cliff Helton, sits at the bar. There’s a 50-year-old photo of Cliff by the cash register. He's out on the Highway, posing alongside his freshly crashed 1936 Ford, wearing a Great Gatsby suit and a movie-star smile. Folks used to refer to Cliff as the Mayor of Jacksboro Highway. He owned dozens of joints, bars, bar-B-Q’s. He stood shotgun over them all, and shot off many a kneecap. They say he gambled most every one away at the flip of a card. As “one of the survivors,” now in his seventies, Cliff doesn’t necessarily like to talk about the old days.

“He’s mellowed some,” says one old-timer at the bar, “but you don’t wanna fool with him. You push him in the corner, do something bad, he gonna do it back worse.”

Jacksboro Highway’s gang warfare of the 1950s created a situation where most of the gangsters shot themselves into extinction. Dozens received gangland executions, their bodies strewn about narrow graves by Lake Worth. Every night, some fool would walk into a bar and announce he was the “toughest man in Texas,” and wait for someone to prove him wrong.

But the professional tough guys had names like Cecil Green, who was shot by gunmen in a Jacksboro nightspot while he counted an extortion haul. Sitting with him was Tincy Eggleston, who escaped the bullet hail. Tincy later had his head blown off by Gene Paul Norris, over robbery money from an alleged Cuban weapons deal. One of the last heavies to go, Norris was gunned down in 1957 by an army of Texas Rangers, state troopers and Fort Worth cops. They chased him into a field after he robbed the Carswell Air Force Base payroll.

The regulars at the last honky-tonks on the Jax still speak quietly the names of those gangsters, 25 years after the last of them were killed. But they can’t figure why the highway is just now being “cleaned up,” two decades later.

The gambling halls and gangster dens all died with the outlaws. But the encroaching fast-food chains that already clutter the Jax will finish off the last of the wild West. The Highway Department will swathe out an eight-lane freeway of corporate shopping malls, and plow over the remnants of Thunder Road.

They will also be eliminating a cowpoke tradition that hasn’t lost a moment from the days when the southeast corner of downtown Fort Worth was known as “Hell’s Half Acre.” It was an outlaw community unrivaled in the West. By the turn of the century there were over 80 whorehouses in business. Fannie Porter’s house of ill repute harbored the Hole in the Wall Gang (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid). Legend has it Bonnie and Clyde stayed in the Right Hotel on North Main Street, now called the Stockyards Hotel. In fact, the suite they are said to have slept in is named after them.

Hell’s Half Acre seemed to move onto Jacksboro Highway by the 1930s. It was still mostly prairie between downtown Fort Worth and Lake Worth. The Jacksboro was built up by the state of Texas to accommodate Carswell Air Force Base and an aircraft factory, bringing thousands of soldiers and plant workers to the area. Cops called it the “Jax Beer Highway” in the ’40s and ’50s, where blue-collar hay hands and packing-house workers got drunk, fought and sometimes killed each other. White kids with money from the Arlington suburbs scored reefers in the back alleys, at a time when marijuana was still a dark secret of Negroes and Orientals. The honky-tonks became off-limits to Carswell personnel when it became evident that cowpokes, Yankee fliers and hay hands made for volatile bedfellows.

The bouncers could usually control the fights at the good clubs. Since World War II, the Rocket Club has been peeling back its canvas roof for summer dancing under the stars. It’s now a white-washed ghost of its former self, where Mexican dances are held. The new highway will demolish it. Top Texas swing bands, including Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, and the Light Crust Doughboys, made it out to the Jax to play such palaces as the Coconut Grove, the Skyliner and the Casino.

Bill Luttrell began playing the Highway that many country musicians avoided, at Hattie’s Silver Dollar in 1946: “It was a real bad place,” says the guitarist, with a hearty laugh. “Notorious for fighting. People from Azle came out there. Two women started fighting one night, then one guy tried to break ’em up and, ’course, everybody in the house jumped on him. I thought we’d never escape. We hit the window with a mike stand and crawled out. When the fight was over, we went back for our PA, which was literally destroyed.

“I played the Skyliner, the last big strip joint [which featured Dallas stripper Candy Barr], on the last night, about 20 years ago. Little Lynn was starring; she’d been part of the Jack Ruby murder trial. I don’t think the police chief much liked her coming here, ’cause they raided us that night at 10 o’clock. Took all the strippers and the club owner to jail. I went down to pick him up. This was a union club, too, so we all got paid; even the strippers were union. Then the Skyliner reopened as a dance joint. The new guy that owned it wrote everybody hot checks, including the beer company, the radio station and newspaper [that ran his] ads, even Ernest Tubb, who headlined opening night.”

The worst thing Luttrell remembers was the night a guitarist named Jimmy Garner went to sub for him at the Rockwood Lounge. “He got killed. He bumped into two mean drunks who got mad and stabbed him.”

The big neon V out on Jacksboro is a dining landmark. Vivian Courtney’s Restaurant still serves great chicken fried anything. During World War II, the establishment was called Harmon’s and served more dinners by car hop than anywhere on the strip. Vivian took over in 1946.

She raised two daughters here and curls an eyebrow suspiciously over Jacksboro’s myths and legends. “Nobody ever bothered us.”

“I think Mansfield Highway was just as dangerous,” drawls her husband Bill, a tall, burly Texan. “For what they say happened on this highway, they coulda went to the moon. All I remember is what I did.”

The Courtneys’ restaurant will likely lose its locale when the freeway is built. They’re not particularly sentimental and feel too old to fight it.

“Time marches on,” says Bill, pointing out that 60 local chain-type businesses signed up in support of the new highway. “When the Highway Department wants our land, they’ll take it.”

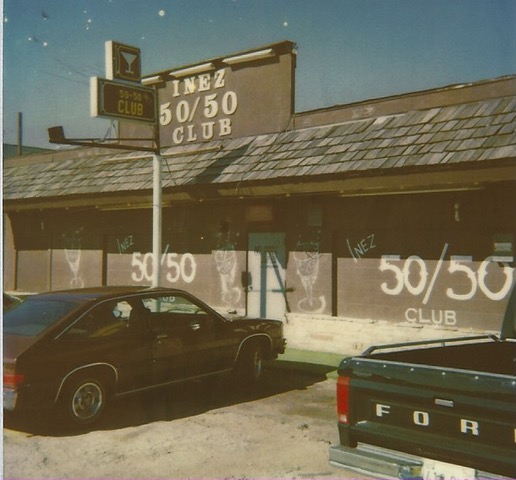

“All I'm doin’ is settin’ and wonderin’,” says Inez, owner of the Inez 50-50 Club, a country-and-Western bar with hot live music. “They didn’t build these new K-marts and Jack-In-The-Boxes to be torn down,” she observes. Touring the strip by car, she points out how all the new fast-food stores seem strategically set more than 36 feet off the road, within legal limits to remain if a freeway cuts up the middle. If the highway goes south, they’ll have to cut down K-Mart, bigger than a football field, which seems unlikely. If they route around north, they’ll steer traffic away, leaving Inez’ club in a back-road shadow. If they cut down the middle, they’ll have to buy her out at “fair market prices” and raze the club.

“Once they build the new highway, business’ll probably be good for a year. Then all these little neighborhood places—people gonna quit comin’, they’ll forget, they’ll hate to get off the highway, it’ll be dangerous. You know how it goes.”

Inez has been on the highway since her youth. Still sexy at 70, she’s on the lookout for a 10th husband. “You can’t be married and run a club. You gotta marry the club.

“I’ve been up and down the road,” she says, steering her luxury car past ghost locations. She points to an empty lot: “That’s where Tincy Eggleston’s gang used to hang out, a bad bunch. They blowed it up, that’s why it’s not there anymore. I guess they’re all pretty near dead, but I don’t like to say anything ’cause they have families.

“That was the Sweet Two Two Five. . . . Up on the hill was the Chateau. After the Fort Worth Stock Show, they’d all be up here at night, playing slot machines, dice boards, girls.

“Oh, I throwed Willie Nelson outta my club many a time,” she remembers, “back in ’50, ’51. He was married to a Mexican girl, and he worked at a service station with my baby boy. He didn't sing—he used to talk sad and play his guitar. Drove me crazy. I had a little old place called the Hayloft, and he’d set up there with his feet hangin’ down. Customers’d say, ‘Please get him down.’ I'd say, ‘Willie, they want you to get out.’ He’d usually go somewhere else, till they run him off, just playin’ for drinks.”

Thirty years ago, out on the Jax, a club owner could send in $12 tax per month to the state. Now, Inez explains, it’s become much harder to run a club. “I sold beer 10 cents a bottle, three for a quarter. Now for each drink I have to send 12 cents to the state. I’m audited in Austin, have to send them three thousand dollars a month.”

Like other club owners on the Jax, Inez claims she never associated or did trade with gangsters. “I have never had any serious trouble at my club. I’ve held a license 47 years, and never had a shootin’ or a cuttin’.” The main troubles Inez had were good-old knock-down drag-out fights, which could only have occurred in a time of prosperity, when the country was happier. Fighting clean was a euphoric tradition, and has gone the way of drive-ins and Buffalo nickels.

“We had lots of rodeo boys, they just loved to fight. With their fists. They were just squares, not characters, who’d get drunk and see who’s toughest. Somebody’d say he could whup anyone on the highway; next thing ya know, they’d meet up the street and make bets. Then they’d come back, buy each other beers. . . . But people won’t fight no more, you’ll get killed, they’ll get a gun and come back to blow yer head off. The honor of fighting has gone. I think it's ’cause of dope, people are more worried, can’t afford a night out anymore. They don’t fool with fighting, just leave ‘em alone or they’ll kill ya.

“I’m getting old,” claims Inez. “I’d like to get out of it. It’s slowed down at the club, I don’t think there’s much goin’ on now on Jacksboro Highway. They might relocate me, but I don’t know where to go. Lord, yes, I will retire if they buy my place. Forty-seven years of this is enough.”

Bobby Sitton remembers Inez’ place as “real dangerous, still lotsa trouble.” But of Massey’s he claims there hasn’t been a fight in several years: “And I was involved in it myself. About fifteen Irishmen come in. First time we ever had any problems with the Irish. They were filthy-mouthed, like they’d finish their beer and th’owed it behind the bar. I ordered ’em outta the place. Then one of ’em th’owed a beer in my face. Nobody th’ows no beer on me. I knocked the hell outta him, smacked him a damn good one, sent him all the way into the jukebox. All his friends got up, and it come out to quite a battle raw. I fought ’em all the way from here to the dance floor, got knocked down a few times myself. My wife jumped off the bar on about five of ’em. The bar girl called the law, and the po-lice got here quick, arrested some of ’em.”

Bobby often visits the Oakwood Cemetery, “the most beautiful cemetery you ever seen.” On the short drive to Oakwood, he proudly points out the dives of yesteryear: “Used to be a place here called Lottie’s—I got shot in the arm by the bartender. We’d had a fallin’ out night before, and he didn’t serve me a beer, so I hit him over the head with a beer bottle. My fault. He shot me in the damn arm, I had to crawl out to keep him from shootin’ again. Then he come outside and still shot at me.

“And there's the old Cartwheel Club, and boy, you talk about fightin’. There was a hell hole if there ever was one. The old man who owned it, name was Grip. Well, one night he decided I needed to leave. So I started out and the sonofagun shot me through the side. I guess I wasn't leavin’ quick enough to suit him. That created a pretty good stink, ’cause I had a bunch of friends who got upset and broke all the windows out.”

Bobby steps out at Oakwood Cemetery, off the highway on Fort Worth’s North Side. This was his childhood playground. “Some of my best friends are buried here,” he laments, stepping slowly over the lumpy green earth. A German shepherd stands guard over a tombstone, his former master. Bobby says they used to hang outlaws right here at the old hanging tree, before burying them. They’d have the trial right across the river at the courthouse.

Oakwood Cemetery provides Bobby’s favorite bird’s-eye view into downtown Fort Worth, across the Trinity River. Tall smokestacks rise up behind the train tracks, where “three niggers fell when they were building ’em. . . and my best friend is buried right there. He was shot between the eyes over a woman, back in the ’50s.

“I still have some pretty good fights back at my motel, mostly with women,” Bobby admits. The Rockwood stands behind Massey’s, and is in considerably worse condition. The rooms run $12.95 per night, and each is equipped with an open space for a 1930’s auto. “I do my best to keep a clean motel, but you can’t always tell if they’re prostitutes till they show their colors.

“Most of ’em white women, fight ya like a dog. I never hit a woman with my fist in my whole life. But I had one that sicced her damn dog on me. We had a knock-down, drag-out fight, she hung her fangs in my arm, almost bit it off—the woman, not the dog. Couldn’t pry her jaws off. Boy, I mean I hit her back. She hadda let go to cuss me. And when she did, we rassled outta my office into the drive, and I’ll be darned if she didn’t sic that dog on me again. Little old poodle. I drug her to the front gate and tossed her out on Jacksboro Highway.

“Well, her blouse got tore off, she didn’t have a bra on, but there wasn’t anything to see, believe me, flat chest. That tickled me. I laughed and said, ‘Lookit there!’ She had two tattoos above where’s supposed to be some female stuff, that said, ‘Have Fun.’

“I’ll tell you one thing, you Jacksboro Highway ho’,’ I told her, ‘you better git down the highway, or next time I’m gonna fight you like a man.’”

The old-timers left on the Jax are so folksy, it’s hard to imagine they were reared in such violent times. “Coldest Beer and Friendliest People in Texas,” reads the logo outside Massey’s 21 Club. But the last of the mom-and-pop joints along Jacksboro—as well as the rest of America—will soon be homogenized into assembly-line malls. All of what is ethnic, regional or historic will disappear in the ongoing corporate Texas chainsaw massacre, dictated by demographic surveys, not human spirit. Fort Worth presents its yearly Pioneer Days in the stockyards, but it is for tourists. The unbroken thread of the real wild West will remain on Jacksboro Highway for about a year.

“Our time’s runnin’ out,” laments Bobby Sitton, hunched over his beloved Massey’s bar. “That highway’s gonna git us.” The state will pay them a “fair market price” for the land and building. “But we’re not getting a damn thing for the loss of customers we built up for 50 years. They’re even taking the Rockwood Christian Church across the street. Used to be the old Massey home place. We sold it to the church with an understanding they’d never start a crusade against us. Now, it looks like they gonna go down the chute, too, with us."

--Josh Alan Friedman